Artists for the Earth

The Art of Protecting National Parks

August 24, 2025

Today is International National Parks day, and as the present Administration in the U.S increasingly describes nature as simply a resource to be monetized, it is more important than ever that we take the time to appreciate our natural reserves as sanctuaries and hosts to essential ecosystems and environments.

In the mid-19th century, artists travelled across the United States, braving the wilderness and summiting peaks to capture the magnificence of the sprawling, untamed West. As photographs, stories, and paintings made their way back to the East, people became passionate about preserving these landscapes before they were destroyed by human development. As a result, Yellowstone National Park became the first national park in 1872.

It is a timely reminder that art has the power to move people to action. Hearing about the importance of preserving national parks can inspire people to advocate for them, but seeing or experiencing natural beauty through an artistic lens creates a uniquely emotional connection between the viewer and the land itself.

Today, national parks welcome artists-in-residence, whose paintings promote conservation efforts and even help raise awareness about the dangers of oil and gas drilling in protected areas. However, it is also important to acknowledge the work of travelling artists and indigenous people in the past. Without the artistic storytelling of these groups, our national parks wouldn’t be what they are today.

Painting a Canvas for Change

One painter who helped change the public perception of national parks in the U.S. was Albert Bierstadt. In the late 1800s, the German American painter depicted Western landscapes in parks such as Yosemite and Yellowstone. His dramatic, spectacular paintings powerfully promoted appreciation for American natural spaces and helped garner national support for public lands. When displayed in exhibitions today, his art moves viewers by conveying a profound connection to the natural world.

National parks exist because people like Bierstadt saw landscapes and environments worth preserving. His work allows many people who do not have the privilege of spending time in these protected areas to still connect with them.

Indigenous Art as a Tool for Conservation

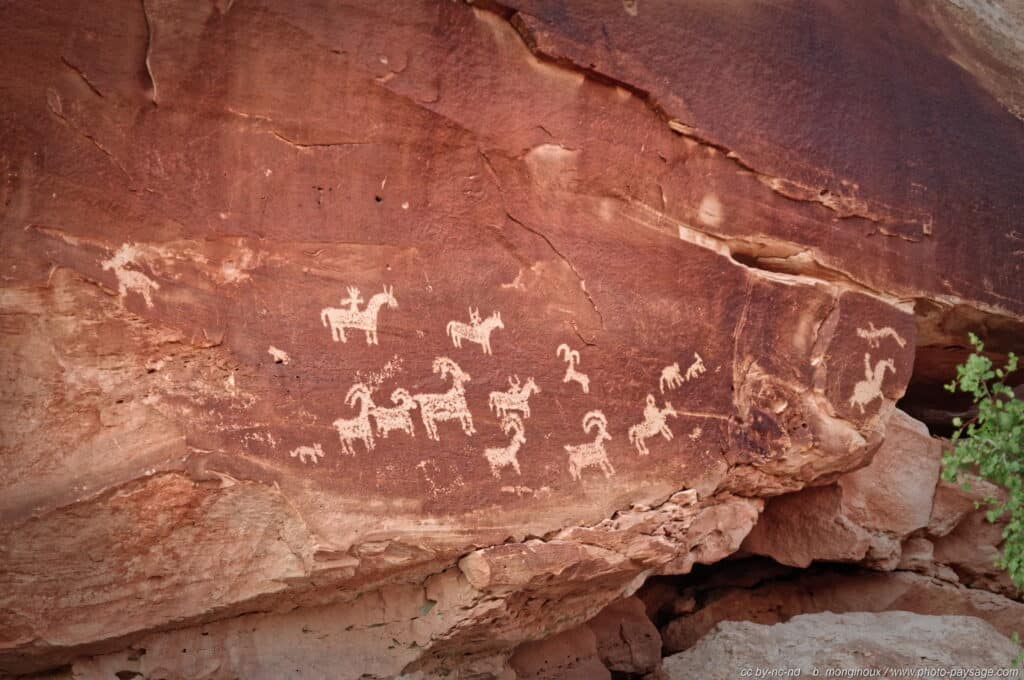

When North American indigenous groups such as the Ute and Puebloan tribes traveled through western landscapes, they left behind drawings that told stories of their culture and the land.

These stone carvings, called petroglyphs, have led to the conservation of land in many areas of the United States. For example, Arches National Park in Utah and Petroglyph National Monument in New Mexico protect drawings so that they can be studied and appreciated. Petroglyphs are visual evidence of changing climates, cultural practices, and historical events, and preserving them keeps the history of the land alive for future generations.

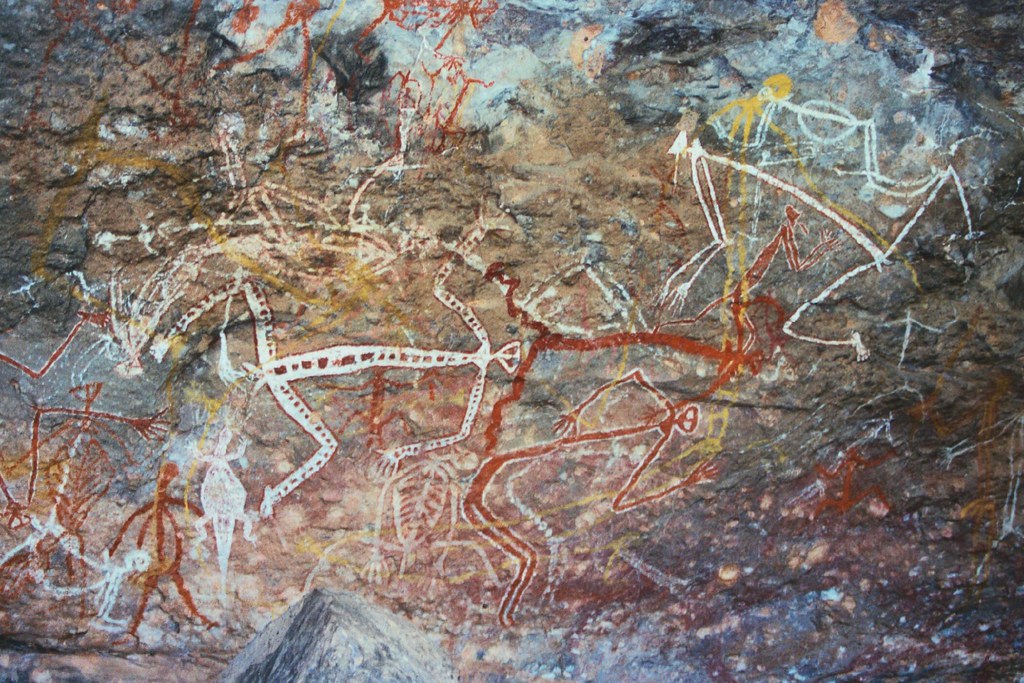

Rock art has played a similar role in the preservation of national parks in Australia. In 2021, a uranium mine located in Kakadu National Park ceased production after decades of protests from Aboriginal owners of the land. When explaining the decision, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said that indigenous rock art in the park should be protected as “a reminder of the extraordinary privilege all of us have, to share this continent with the world’s oldest continuous culture.”

The Hills are Alive with the Sound of Music

In addition to paintings and carvings, music written in support of national parks has touched listeners and sent them thronging to preserved lands. In celebration of the National Parks Service Centennial in 2016, parks across the United States held concerts to celebrate the milestone.

They featured classical music by indigenous musicians, covers of famous compositions, and contemporary performances complementing a backdrop of dramatic canyons and towering mountains. The concerts contributed to an astounding 331 million visitations to U.S. national parks in 2016.

Another example of the role of music in preserving national parks is the song “Grýlukvæði” by Icelandic musician Valgeir Sigurðsson. In the 1990s, projects to build hydropower dams in the Icelandic Highlands threatened ecosystems, geological formations, and cultural heritage. Songs like “Grýlukvæði” were written to evoke an emotional response to the environmental crisis, and they played a role in bringing awareness to the harms of some of these projects. In 2008, Vatnajökull National Park was established to protect a portion of the Highlands from damaging infrastructure.

Artistic storytelling from artists around the world shares the grandeur of national parks with people who otherwise wouldn’t be able to experience it. Every stroke of a brush, chip of a rock, and pluck of a string tells the history of the lands people deemed too precious to destroy.

A striking depiction of a park or historical event stirs emotions that can change perspectives and drive people to activism.

If you can’t visit a park this International National Parks day, take time to appreciate them by learning more about the artists who helped preserve the parks near you. To help keep them available for future generations, visit our Climate Education page to find ways to teach others about the importance of conservation.

If you care about the environment, and are in the U.S., we need your voice. Add your name to our public comments on the EPA’s intentions to gut the agency’s ability to regulate pollution due to climate change, also known as the Endangerment Finding.

The time to act and protect nature is now. Do it for our park’s right to exist and for your children’s future right to roam free in unspoiled nature.

This article is available for republishing on your website, newsletter, magazine, newspaper, or blog. The accompanying imagery is also cleared for use with attribution. Please ensure that the author’s name and their affiliation with EARTHDAY.ORG are credited. Kindly inform us if you republish so we can acknowledge, tag, or repost your content. You may notify us via email at [email protected] or [email protected]. Want more articles? Follow us on substack.